Achilles Tendonitis is a common source of pain for runners, basketball players, and other athletes. The Achilles tendon connects your calf muscles to your heel bone. It’s the largest tendon in your body, and it acts like a rubber band that assists with running, jumping, and other explosive movements. If you play running sports or other activities that can strain your Achilles tendon, you are at risk of developing Achilles tendonitis. This painful injury typically develops gradually over time and often goes unnoticed until it becomes a problem.

Overview of Achilles Tendonitis

The Achilles tendon is one of the most commonly injured tendons in the human body. It has become one of the most prevalent musculoskeletal conditions as a result of the growing number of individuals taking part in recreational and sports activities.

The Achilles tendon is one of the most commonly injured tendons in the human body. It has become one of the most prevalent musculoskeletal conditions as a result of the growing number of individuals taking part in recreational and sports activities.

Doctors and health professionals are searching for fresh information on Achilles tendon issues to enable preventive and therapeutic interventions. This condition can be debilitating if left untreated. Simple exercises are an efficient preventive and defensive approach against this condition.

The Basics of Achilles Tendonitis

Achilles tendonitis was the term used to describe a spectrum of Achilles tendon injuries, ranging from signs of inflammation and tendon rupture to bone spur formation in the heel and swelling of the fluid-filled sac found at the back of the heel bone.

Astron and Rausing (1995) found that degenerative changes in tendon fiber structure were present in 90% of Achilles tendon biopsy samples.

Basic Anatomy of Achilles Tendon

In Greek mythology, Achilles was the greatest and strongest warrior of the Trojan War. Achilles’ Achilles heel was his only vulnerable spot, although his strength was immense. The Achilles tendon shares similar features and workings with Achilles. It is the largest, thickest, and strongest tendon in the human body. According to Dubin (2005), the Achilles tendon can absorb eight times the body weight from a 900-foot jump per mile as a result of its ability to absorb ground forces.

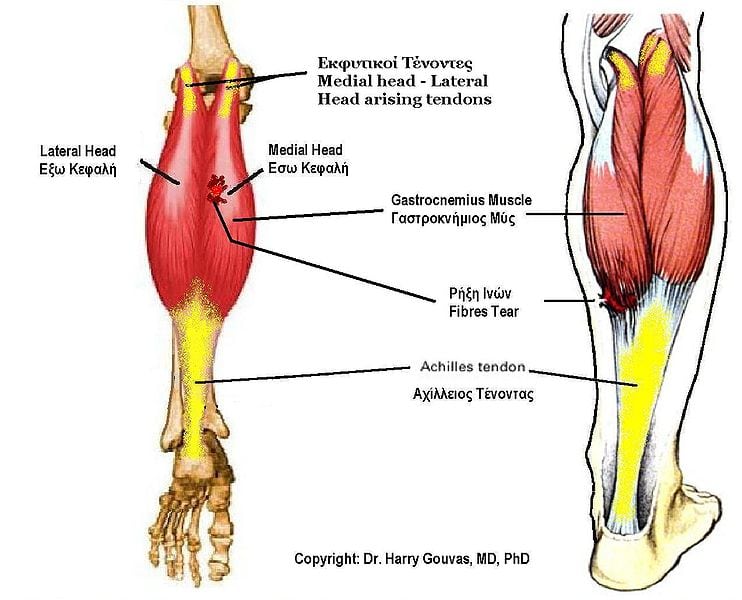

Merging of the Gastrocnemius Muscle and Soleus Muscle

The Achilles tendon runs from the top of the heel to the back of the calf. The calf is mainly composed of two muscles: the gastrocnemius muscle and soleus muscle. The tendinous portions of these muscles merge to form the Achilles tendon, which then attaches them to the heel bone. The gastrocnemius, the largest and most superficial of the calf muscles, is the primary muscle force during running and walking. The soleus muscle is underneath the gastrocnemius. It supports the upright position when standing and increases the angle between the foot and the ankle.

Unique Features of the Achilles Tendon Sheath

The Achilles tendon, despite its toughness, can glide due to its sheath structure. It does not have an actual tendon sheath; instead, a thin paratenon, a double-layer synovial cell sheath, surrounds it.

The outer layer of the paratenon is continuous with fat tissues. Its inner layer is continuous with epitenon, which directly contacts the Achilles tendon. The space between the epitenon and paratenon contains a lubricating fluid that glides the Achilles tendon when running or walking.

Collagen and the Achilles Tendon

The Achilles tendon relies on type I collagen, a tough fibrous protein, to withstand pressure and transfer forces. As tendons degenerate, type I collagen fibers are replaced with type III collagen fibers, which are less sturdy than type I fibers.

Blood supply to the Achilles Tendon

Compared with other tissues, the Achilles tendon has a limited blood supply, mainly derived from the blood vessels traversing the Mestinon, the layer found between the paratenon and epitenon. Blood is supplied directly to the muscle through which the tendon runs and the heel bone at the tendon’s terminal insertion site from the tendon’s forces.

Biomechanics of the Achilles Tendon

The gastrocnemius-soleus musculotendinous unit connects muscle and bone by crossing the knee, ankle, and lower ankle joints. It buffers large loads and stresses by absorbing them during running and walking. A strong, flexible, and elastic Achilles tendon absorbs a large amount of force and stress by acting as a buffer between the calf muscles and the heel bone (Maffuli et al., 2004).

Research showed that healthy tendons could stretch to 4% of their original length before being damaged. Rupture is more likely if the pressure exceeds 8%.

Thank you very much for reading part 1 of Achilles Tendonitis and Exercises. I will be back with part 2 very soon.

Have a great day.

Rick Kaselj, MS

Here is a video related to Achilles Tendinitis:

Heel Drop Exercise

Here are some of the other Injury and Exercise Reports that I have done in the past:

- Shoulder Pain

- Plantar Fasciitis Exercises

- ACL Exercises

Here are some other articles that may interest you relating to Achilles Tendinitis:

- The Rise of Tendinosis

- How Olive Oil and Candle Light Can Help with Achilles Heel Tendonitis

- The Best Hiking Stretch to Prevent Ankle & Knee Injuries – Heel Drop